Food for thought

From left: Writer Leung Man-tao, Chuang Tzu-i and food critic Shu Qiao share their views about the spirit of making delicious food during the recent Open Day events in Beijing. [Photo by Yang Ming/For China Daily]

Discussions on restaurants, eating habits and cooking highlight Open Day events in Beijing.

Chuang Tzu-i from Taiwan was studying anthropology in the United States about 12 years ago. One day the doctoral candidate came across Cambridge Cookery School in the neighborhood of her lodging. Watching through the window, she could see a busy class shrouded in steam.

It was the sixth year of her PhD program when she was preparing for her final dissertation.

In a surprise move, she quit university and registered as a student at the cookery school, a decision unimaginable for many Chinese, especially a decade or so ago.

Chuang eventually became a popular blogger, and her writings about the experience at the cookery school and her observations of kitchen operations at ritzy restaurants fascinated her online followers. In 2008, she published her first book, Anthropologist in the Kitchen.

She shared her stories with more than 200 audience members recently at Open Day, a series of events organized by Vistopia, a sister brand of the publishing brand Imaginist.

"I never regret my seemingly imprudent decision. ... In the last 10 years, what I did has gradually been understood and accepted by more people. I know now an increasing number of young Chinese people try to pursue the meaning of life according to their own will," Chuang says.

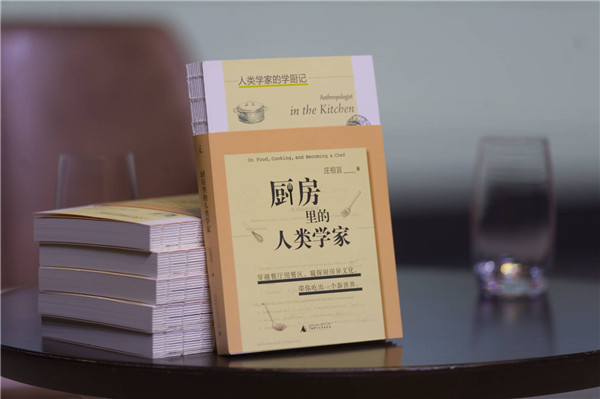

Anthropologist in the Kitchen by Chuang Tzu-i. [Photo by Yang Ming/For China Daily]

Writer Leung Man-tao, who plans the Open Day events, says they try to turn abstract ideas to real experiences.

At this year's events that ran through March, participants enjoyed a selection of food, music, film, coffee, tea and chats with people from the creative industry.

"One (goal) is how to improve people's humanistic education, including how to think more reasonably about life, society and the world," Leung says of the events.

"The second is about how to attain a more comprehensive and compassionate sensibility to feel the other's existence, and details in ordinary life that are worth digging into so as to enrich one's life."

Liu Ruilin, the founder of Imaginist, further explains that without a solid physical life as the foundation, spiritual products will appear pale and weak.

Chuang was invited to talk about the spirit of making delicious food and enjoying it with Leung and food critic Shu Qiao, since food and restaurants are an important part of an ideal life.

"Cooking is a very personal and relaxing experience, so I don't like cooking contests that try to judge a dish by a single standard," Shu says.

Shu has an opinion on restaurants, too. She says some restaurants "make cooking a show".

Tea sets are among the objects on show during the Open Day events. [Photo by Yang Ming/For China Daily]

"It makes the food expensive because the charge includes the presentation," she says.

Leung says restaurants also should bear in mind the emotional health of chefs. "Otherwise, eating would become a suffering" for the customers, especially if they realize that the staff isn't happy. In such a case, cooking could become a way of social alienation even for professionals, the three speakers agree.

In the kitchens of some star-rated Western and Asian restaurants, chefs work like they're in an army, highly cooperative and efficient, but each person performs a single task, say, cutting fish, boiling rice or chopping onions, Chuang says.

In some restaurants, the employees are not allowed to talk to each other or listen to music, making the work environment unhappy, she adds.

That's not to mention, many cooks have to go to the gym to keep in shape, Shu says.

But professionalism in Western cooking has gradually influenced Chinese restaurants and cookery schools. Some cooks who graduate from professional schools still seem to add too many processed condiments in dishes, making them "strong in flavor, oily and often unhealthy", according to Chuang.

"It seems that in the last 30 years, Chinese people in general have started to like food with strong flavors-salty, oily and spicy, like Sichuan and Hunan cuisines, both of which are famous for being spicy," Leung says, adding that even Sichuan cuisine itself has grown stronger in flavor.

"People in different cities all like eating malatang (skewered meat, vegetables and tofu products boiled in spicy broth and cooked in a fiery sauce) as a nighttime snack," he says.

Shu agrees: "No matter which tourist spot around the country you go to, there are always foods like barbecued squid or Taiwan sausage. It's like all the ancient towns in China now have a similar look."

This is because strong-flavored dishes can be easily replicated everywhere, Chuang says.

Some major sauce makers also sponsor cookery schools and encourage trainers to use their condiments.

"Which means, as all the flavors are simplified, our tongues generally lose the sensitivity to different tastes. We are seeing the same kind of things and eating the same kind of food, which can make our thoughts simple in the long run," Leung says.

These days, many people like to go to popular restaurants and post photos on social media.

"Enjoying the food is not as important to them as taking photos and posting them online," Leung says.

Shu continues, "People say that it is a time when people are given diverse choices, but I don't see that."

People tend to go to the same places for food or sightseeing when they visit a city. Otherwise, they may feel they've missed out, she adds.

"That's why we emphasize sensitivity and diversity with our events," Leung says.